Cryptographic Identity

From Keys to Graphs

Part of the Exploring the Sovereign Web series

- Content Addressing

- Cryptographic Identity

- Exploring Privacy

In the previous exploration, I looked at content addressing and how cryptographic hashes let us verify data without trusting a central host. That solves the problem of integrity, but it leaves a massive gap regarding authenticity.

I can write a document, hash it, hand you the fingerprint, and claim it was written by Albert Einstein. The hash proves the file hasn’t changed since I created it, but it proves absolutely nothing about who created it.

This forces us to ask a harder, more human question: how do we establish identity in a world without gatekeepers?

For decades, public-key cryptography has given us the primitives for answering this question. A user generates a private key and a corresponding public key. Messages signed with the private key can be verified by anyone holding the public key. The math is solid, and it has been for a long time.

What the math did not give us was a usable system for real people, real devices, and real failure modes. That gap between elegant primitives and lived reality is where most identity systems have struggled.

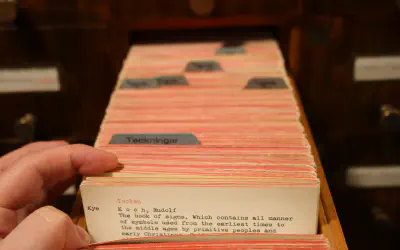

The first era: the key ring (PGP)

In the early 1990s, PGP (Pretty Good Privacy) attempted to turn public-key cryptography into a decentralized identity system. It introduced the idea of a “Web of Trust”, where individuals could vouch for each other without relying on a central authority.

PGP didn’t fail because the cryptography was weak. It failed because the system assumed humans would behave like careful systems administrators.

Social friction

In the PGP model, identity wasn’t established by default. It had to be earned. Proving you were “Alice” required other people to manually verify you, often in person, by comparing key fingerprints and government IDs at so-called key-signing parties.

As a social experiment, this was interesting. As a global identity mechanism, it was impractical. It was slow, geographically constrained, and demanded that users reason about abstractions like trust levels and fingerprints that never became intuitive.

Technical weight

On top of the social friction, the technology itself was heavy. PGP relied on RSA keys—massive 2048 or 4096-bit blobs of math that were slow to generate and cumbersome to move. You didn’t just “have” an identity; you had to carry it around as a file, protecting it like nuclear launch codes.

Managing these keys required an understanding of Certificate Authorities (CAs) or complex manual key management that was simply out of reach for anyone who wasn’t a dedicated systems administrator. This weight ensured that strong cryptography remained a niche tool for the paranoid, rather than a foundational utility for the public.

Static identity and the revocation problem

PGP identities were effectively static files. You generated a key pair, stored it somewhere, and that blob represented “you” indefinitely.

If you lost it, your identity was gone. If it was stolen, you had to revoke it. In theory, revocation was simple. In practice, it depended on a loose federation of key servers that were often unreliable and out of sync.

The result was a dangerous failure mode: compromised identities that lingered. A stolen key could continue to be accepted by parts of the network long after its owner knew it was unsafe. Identity became something that could die, but not fully disappear.

The second era: device-centric identity

Modern secure messaging systems took a more pragmatic approach. Instead of asking users to manage long-lived identity keys, they shifted identity to the device itself.

When you install an app like Signal, it quietly generates keys for that device. You don’t attend ceremonies. You don’t manage files. The system assumes the device is the identity.

We see a version of this every day with WebAuthn (FaceID/TouchID). It’s incredibly secure but fundamentally locked to the hardware. The “Graph” approach is what lets us bridge that security into a cross-device world without a “Log in with Google” button.

Trust on first use

These systems rely on Trust On First Use (TOFU). The first time you communicate with someone, you accept the key presented to you. From that point on, the system watches for unexpected changes.

If a key changes, the software warns you. This moves complexity away from setup, which everyone experiences, and into recovery, which is relatively rare.

This trade-off worked. It brought strong cryptography to billions of people. But it also made identity ephemeral. Lose your phone and you often lose your history. For chat, that’s acceptable. For long-lived systems meant to outlast devices, it’s not.

The third era: identity as a graph

If we want identity to survive device churn and decades of use, we need a different structure. The emerging pattern is to treat identity not as a single key, but as a graph of authority.

Separating authority from activity

At the root of the graph is a master key. This key represents the identity itself and is used rarely, if ever. Its only role is to authorize other keys.

Below it are device keys. Each device generates its own key pair. The master key signs short certificates saying which device keys are currently allowed to act on its behalf, and for how long.

This changes the revocation story completely. If a device is lost or compromised, the master key issues a revocation. Anyone verifying a signature can look at the identity’s history and see exactly when that device was authorized and when it was revoked.

In a decentralized system, this history is usually an append-only log of signed operations. By verifying the log, I don’t just see a key; I see a self-sovereign audit trail. There is no need for global coordination. Verification becomes local and deterministic.

Digital identity needs analog durability

Long-lived identity fails most often during recovery. Hard drives fail. Password managers break. Files are lost.

One of the more practical insights to come out of the cryptocurrency world is that paper is a surprisingly good storage medium. Using standards like BIP-39, a master key can be encoded as a short list of words that a human can write down and store physically.

Ink doesn’t suffer bit-rot. Paper doesn’t depend on file formats. It’s crude, but it’s durable.

Social recovery

Paper alone is still a single point of failure. To mitigate that, systems increasingly use Shamir’s Secret Sharing to split a master key into multiple shards.

Any subset of those shards can reconstruct the key, while individual shards reveal nothing on their own. By distributing them among people or institutions with “independent spheres of trust” or “non-colluding relationships”, recovery becomes possible without re-introducing a central authority.

This approach acknowledges trade-offs openly. It replaces the certainty of permanent loss with a manageable risk of collusion. That’s a trade many systems are now willing to make.

Where this leaves us

Centralized identity didn’t dominate because it was malicious. It dominated because it solved onboarding, recovery, and support in ways early cryptographic systems could not.

What’s changed is not the math, but the architecture around it. By treating identity as a graph of delegated authority, anchoring it in durable recovery mechanisms, and designing for revocation from the start, we can finally build systems where identity survives contact with time.

This is still hard. It’s still easy to get wrong. But it no longer feels out of reach.

But identifying ‘who’ someone is doesn’t guarantee that only they can read your data. Whether we are sending a message or storing a file for a team, we need a way to lock the data so that only authorized identities can unlock it. This is what I will explore next.