Deriving Your Real Architectural Drivers

Great architecture does not start with a solution. It starts with a deep, honest understanding of the problem

Part of the From Patterns to Practice series

- The Architect's Compass

- Deriving Your Real Architectural Drivers

- The Architect's Toolbox

- The Decision Engine

- The Spike

- Documenting your decision

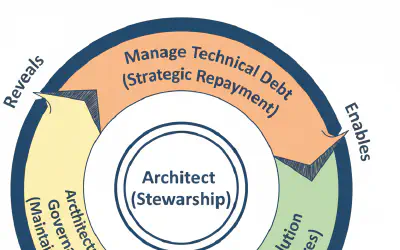

- An Architect's Work is Never Done

The Danger of Vague Goals

In the workshops I lead, the first instinct of many participants is to jump straight into a solution. “We need microservices!” or “A monolith is faster!” But that is putting the cart before the horse.

Why? Because terms like “speed” and “scalability” are too vague. They are labels for a problem, not a description of it. You cannot compare solutions against generic concepts; you must evaluate them against the specific, concrete risks of your business.

Before you can open the toolbox, you have to map the territory. This is where we derive the real architectural drivers you need to design for.

From Risk to Requirement

You start by mapping the critical business workflow to find where the risk is concentrated. For CityPulse, the entire business risk is concentrated in the ticket purchasing flow during a flash sale. Everything else—user profiles, event browsing, newsletters—is secondary. If the checkout fails during a sale, the company dies. Period.

Architect's Log

Most systems do not need to scale everywhere. Identifying this narrow point of pressure is half the battle. We are not solving a generic “scalability” problem; we are solving a very specific “transactional throughput” problem.I use the Quality Attribute Scenario (QAS) to structure this thinking. It is a simple story format that forces you to be specific.

In my workshops, I have the participants walk through it like this:

- Source: Who is creating the problem? (e.g., A large number of concurrent users).

- Stimulus: What are they doing? (e.g., Attempting to purchase tickets).

- Environment: What is the context? (e.g., During a flash sale).

- Response: What must the system do? (e.g., Process the purchases successfully).

- Response Measure: How do we define success? (e.g., At least 1,000 transactions per second).

By filling in these five blanks, you move from a vague “We need to scale” to a concrete, testable requirement:

“A large number of concurrent users (Source) attempt to purchase tickets (Stimulus) during a flash sale (Environment). The system must process at least 1,000 purchases per second (Response Measure).”

This is the “aha!” moment for many architects. You are no longer guessing; you are defining the exact scale of the cage you need to build.

Architect's Log

A word of caution: while these numbers look precise, they are often just well-informed guesses. Will it really be 10,000 users, or 20,000? Is a 1.5-second page load really the magic number, or is 1.7 acceptable? Don’t get trapped by the precision of your own metrics. The goal of a QAS isn’t to predict the future perfectly; it’s to create a reasonable, shared target that is an order of magnitude better than a vague feeling.Key Takeaways:

- Specifics over Labels: “Scalability” is just a label. A 1,000 TPS requirement is a target.

- Focus on the Pressure Points: Find the specific workflow where the business risk is concentrated.

- The QAS Tool: Use the 5-part scenario structure to turn vague fears into concrete engineering requirements.

Mapping the drivers is architecture

Until you have these concrete scenarios, you are not doing architecture; you are doing guesswork. You might build a perfectly scaled “User Profile” service while the checkout flow is still a single-threaded bottleneck.

Now that we have mapped the territory and defined our real drivers, we can finally open the toolbox. In our next post, we will evaluate the three foundational architectural styles against these specific scenarios.