Documenting your decision

Documenting and Communicating Your Decision

Part of the From Patterns to Practice series

The Decision is Made. Now What?

You have analyzed the styles, run the numbers, and picked a path for CityPulse. But a decision that only lives in your head—or on a static spreadsheet—is a ticking time bomb.

What happens in six months when a new developer joins the team? What happens in a year when you need to evolve the system? This is where most teams fail. They suffer from “Architectural Amnesia.” Decisions are made, context is lost, and future teams are left wondering why on earth you did it this way. That leads to bad changes, technical debt, and a frustrated team.

The final step in the framework is to document and communicate the why of your choice. For this, I use two practical tools: Architectural Decision Records (ADRs) and the C4 Model.

Architect's Log

Let us be honest for a moment. The process we just walked through for CityPulse was clean. The drivers were clear, the options were distinct, and the weights were agreed upon. The real world is never this tidy. In a real project, you would be dealing with a dozen other factors: the legacy system you have to integrate with, the political influence of the VP who loves a certain technology, and the vague, shifting requirements from marketing. The framework we are using is not a magic formula that erases this complexity. It is a tool to bring a sliver of clarity and rationality to that complexity. It is a way to force the hard conversations and to make a defensible choice, even when the data is imperfect and the pressures are immense. Do not mistake the clarity of this story for the simplicity of the job.Capturing the “Why”: Architectural Decision Records (ADRs)

You do not need a 100-page document that no one will ever read. You need a record of why you did not do the other thing. Think of an Architectural Decision Record (ADR) as a journal entry for your system—a way to explain yourself to the team that will inherit this code in two years.

Here is a practical template:

1# Title: Event-Driven Architecture for Core Ticketing Flow

2

3**Status:** Accepted

4

5**Context:**

6

7We need an architecture for CityPulse that can handle high-throughput,

8transactional spikes during major concert sales, while allowing us to launch

9within a tight, 3-month deadline. A monolith risks failing under load, while

10a traditional microservices approach is too complex to build quickly.

11

12**Decision:**

13

14We will adopt an Event-Driven Architecture for the core ticketing workflow.

15The initial implementation will focus on the `TicketPurchaseRequested` event

16and the services that consume it. We will precede this with a two-week,

17time-boxed spike to prove out the technology and the ability of our team to manage

18it.

19

20**Consequences:**

21

22* **Positive:** This style directly addresses our critical scalability and

23reliability drivers. It decouples our services, making the system more

24resilient to individual component failures. It provides a foundation for

25future, real-time features.

26

27* **Negative:** We accept the significant upfront complexity and learning

28curve associated with asynchronous systems and eventual consistency. This poses

29a risk to our timeline, which we are mitigating with a focused spike. Debugging

30and end-to-end testing will be more difficult than in a monolith.

Architect's Log

People often get hung up on the ADR format. It does not matter. What matters is that you write it down. The most valuable part of an ADR is the ‘Consequences’ section. Being honest about the downsides and trade-offs of your decision is a sign of a mature architect. It tells future teams what problems they should be looking out for and what you were optimizing for. Also, remember that an ADR is a living document. The ‘Consequences’ section, in particular, should be updated as you learn more after the decision is implemented.Communicating the “What”: The C4 Model

Now that you have captured the ‘why,’ you need to explain the ‘what.’ How will this new system look?

Do not try to show everything to everyone. You will end up with a “big ball of mud” diagram that looks impressive on a wall but tells nobody how the system actually works. The solution is to create different maps for different audiences. I use the C4 Model to structure this.

For the CEO, start at Level 1: The System Context Diagram. This is a high-level map of the world. It shows CityPulse as one box in the middle, with the users and systems it talks to. It is the big picture and nothing more.

For the engineering team, you zoom in to Level 2: The Container Diagram. This map shows the technical building blocks inside the system—the web apps, message brokers, and databases. It shows how the major pieces of your architecture actually fit together.

You can zoom in further, but for communicating a new style, these first two levels are where the battle is won.

Key Takeaways:

- Write it down or lose it: A decision is only as good as its communication. Fight “Architectural Amnesia” by recording the context.

- Context over Content: Use lightweight ADRs to document why you made the choice, especially the trade-offs you accepted.

- Maps for Audiences: Use the C4 Model to show the right level of detail to the right people.

A Decision, Justified

Execution of the framework is complete. You have moved from a business problem to a data-driven, documented, and justified plan for the foundation of CityPulse. This is the repeatable process for high-stakes architectural choices.

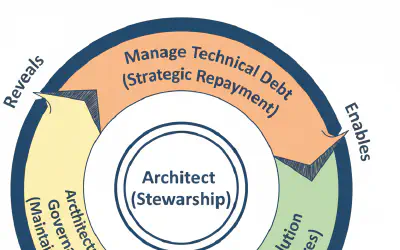

But is the job over? Not even close. Architecture is a living thing. Now that the foundation is set, we must move to the next challenge: protecting it against the slow erosion of time. In our next series, we will move from Practicing Architecture to Codifying it.

What is the biggest challenge you face with documentation in your team? Have you ever used ADRs or C4? Share your experiences in the comments.