The Architect's Compass

A Tale of Speed vs. Scale

Part of the From Patterns to Practice series

In the workshops I lead on software architecture, I always start with a specific scenario. I call it ‘CityPulse,’ and it represents the first major test any new architect faces: the fundamental conflict between the business and the engineering team.

Here is the setup: The CEO catches you in the hallway. “Our main competitor launches their platform in four months. We have to beat them. I need our platform live in three, no exceptions.” An hour later, your lead engineer finds you at your desk. “That timeline is aggressive,” she says. “My fear is that the moment a popular concert goes on sale, our whole site is going to crash and burn. We need to build this thing to scale.”

The business is demanding speed. Your engineering team is demanding stability. Both are right.

Learning how to navigate this tension is the job. It is the true essence of software architecture. This post—and this entire series—is a distillation of that workshop, designed to help you build a professional vocabulary for these conflicts and a framework for making the trade-offs explicit.

From Business Problems to Concrete Drivers

When you are caught in this conflict, the worst thing you can do is jump straight to a solution. You start by translating these business pressures into a professional vocabulary—giving them names like Time-to-Market, Scalability, and Reliability. In the industry, we call these “Quality Attributes.” But let us call them what they really are: the constraints that actually matter.

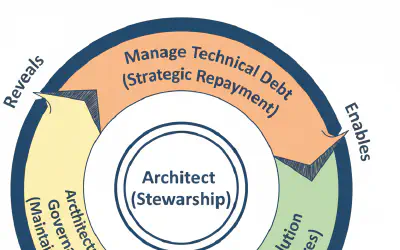

Your Real Job: The Art of the Trade-Off

Software architecture is not just about being the technical expert. The architect’s job is to strip away the technical anxiety and find the actual business impact. You stand in the middle of this tension to force a conscious choice by making the trade-offs explicit.

Architect's Log

I have seen too many projects fail because they never had the hard conversation. The business wanted one thing, the engineers wanted another, and instead of forcing a decision, they tried to do both and ended up with a mess. Your first job as an architect is to force that conversation to happen, and naming the Quality Attributes is how you start. It gives you a professional vocabulary to turn a vague cloud of anxiety into a concrete list of trade-offs that can be properly debated.This is not about guessing. It is about finding the actual cost. If the site goes down during a flash sale, does the company lose $5,000 or does it lose the trust of its entire user base before it even gets off the ground? If nobody can name the price of failure, nobody can make an architectural decision.

Your job is to expose these questions and guide the organization to an answer, so they actively choose their priorities, rather than stumbling into a disaster by accident.

Sketching the Extremes

Once you have concrete drivers, you need to see the trade-offs you are working with. A good way to start is by exploring the two most extreme options.

On one end, you have the monolithic application. It serves your Time-to-Market goal perfectly, but it carries the risk of a single point of failure and scaling inefficiencies.

On the other hand, you could break the system into independent services—a microservices architecture. This serves your scalability driver, but it is almost certainly a launch-day killer for a three-month deadline.

These two extremes are not your only choices, but exploring them defines the battlefield: you are fighting a war between speed and scale.

Architect's Log

Be careful of the ‘false dichotomy.’ The world is not just monoliths and microservices. These are poles on a spectrum. In the real world, many of the best solutions are hybrids: a ‘well-structured monolith’ with clear internal modules, or a ‘mini-services’ approach with a few, coarse-grained services instead of dozens of tiny ones. Exploring the extremes is a tool for analysis, not a menu to order from.Key Takeaways:

- The Translation Layer: Stop talking about “speed” and “scale.” Name the Quality Attributes (Time-to-Market, Throughput). If you cannot name the driver, you cannot defend the design.

- Understanding Pressure: Architecture is not about generic best practices; it is about identifying the specific business risk and designing to mitigate it.

- Extreme Analysis: Sketching the extremes (Monolith vs. Microservices) is not about picking one. It is about defining the range of trade-offs you have to navigate.

Your job is choosing the right pain

The choice is not about which technology is “best.” It is about which set of trade-offs you are willing to accept to serve the unique, conflicting needs of your business.

Most teams stumble into a disaster because they do not actively choose their priorities. They try to “scale everything” while launching “tomorrow,” and end up with a mess that achieves neither.

In our next post, we’ll move from these vague concepts to a tool that turns “scalability” into a concrete, testable requirement: The Quality Attribute Scenario.

Further Reading

- Software Architecture: The Hard Parts by Neal Ford, Mark Richards, et al. The definitive book on the nature of architectural trade-offs.

- Martin Fowler’s article on the Utility vs. Strategic Dichotomy, which adds excellent nuance to the “build it fast vs. build it right” conflict.

In the comments below, tell me about a time you faced a conflict between “building it fast” and “building it right.” How did you navigate it?