The Decision Engine

Making Data-Driven Architectural Choices

Part of the From Patterns to Practice series

From Qualitative to Quantitative

In my workshops, this is usually the point where the room gets quiet. We’ve analyzed the styles, we’ve debated the trade-offs, and we’ve looked at the candidate architectures for CityPulse. The dilemma is real:

- The Monolith wins on speed.

- Microservices wins on scale.

- Event-Driven wins on resilience.

This is where “gut feelings” usually take over. But a gut feeling is not a defensible architectural strategy. You cannot justify a $2M infrastructure project to your board because it “felt right.”

To make a professional decision, you need to move beyond qualitative debate and into quantitative analysis. This post is about the two tools I use to break the tie: the Pattern Profiling Scorecard and the Weighted Scoring Matrix.

Tool 1: The Pattern Profiling Scorecard

I use the Pattern Profiling Scorecard to visualize how each architectural style handles the Quality Attributes that matter to us. It’s a way to map the theory onto the reality of our specific drivers.

Based on your deep analysis, you fill out the scorecard:

This scorecard is a powerful summary. It takes your analysis and distills it into a format that clearly shows the conflicting profiles: the Monolith is strong on the cost/speed axis, while the distributed styles are strong on the scale/performance axis.

Weights are the Business Truth

To break the tie, you have to apply the actual priorities of the business. Not all drivers matter equally. Assigning a percentage “weight” to each driver is how you turn a technical debate into a formal declaration of what the organization cares about most.

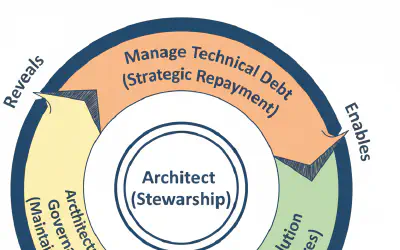

Facilitating this conversation—forcing the CEO and the Lead Engineer to agree on these percentages—is often the most valuable thing you can do as an architect.

After considering the existential pressures on CityPulse, you assign the weights:

- Time-to-Market (40%): The CEO’s deadline is critical for survival.

- Throughput Scalability (30%): The engineer’s fear of a crash is equally critical.

- Reliability (15%): Essential for user trust and payments.

- Initial Cost (10%): Upfront CapEx matters for a startup, but survival matters more.

- Performance (5%): Under load, this is important, but partially covered by scalability.

With your scores and your weights, you run the simple multiplication (Score x Weight = Weighted Score).

After summing the results, the data gives you a clear, if surprising, winner. The Event-Driven style emerges with the highest score of 3.85, narrowly beating the Monolith at 3.80.

Architect's Log

This result makes me pause. The data points to Event-Driven, but my experience tells me this is where a purely mechanical process can lead you astray. The matrix is a powerful tool, but it is a simplification; the real world is never so clean.The matrix provides a data-informed hypothesis, but it is not the final answer. It does not fully capture all real-world complexities—like political pressures, team skills, or shifting requirements.

Crucially, the biggest missing piece here is Team Proficiency. If your team has not done Event-Driven before, the “mathematical winner” is actually a huge risk. You do not blindly accept the result; you use it to frame the next conversation.

Key Takeaways:

- Stop Guessing: Use scorecards and weights to move beyond qualitative debate. If you cannot quantify your choice, you cannot defend it.

- Weights Connect Code to Cash: Assigning business weights is what connects your technical choice to the actual business strategy.

- The Matrix is a Hypothesis: Never treat the final number as the truth. External factors like team skills matter more than a cell in a spreadsheet. Always validate high-risk winners with a spike.

Choosing the right pain

Choosing an architecture is not about being “right.” It is about being justifiable. By following this process, you have moved from a “gut feeling” to a defensible strategy that the business has signed off on.

But even with the best data, a decision on paper is still just a hypothesis. In our next post, we will move from the spreadsheet to the code: running an Architectural Spike to prove the design before you bet the company on it.

Further Reading

- Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman. A masterclass on the cognitive biases that can influence stakeholders during the critical process of assigning weights to drivers.