The Spike

Where Theory Meets Reality

Part of the From Patterns to Practice series

Where Theory Meets Reality

In my workshops, this is the moment where the energy shifts from academic debate to real-world anxiety. You’ve done the analysis. You’ve run the numbers. You’ve presented your data-driven choice to the CEO.

But as you walk back to your desk, a new thought hits you: What if we cannot actually build this?

For CityPulse, the Weighted Scoring Matrix pointed to the Event-Driven style. But the victory was by a razor-thin margin, and it came with a huge, unquantified risk: the team has never done asynchronous, distributed programming before.

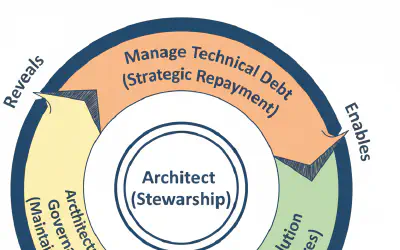

An architect’s job is not just to make the decision; it is to de-risk it. This is where we use the Architectural Spike.

The Mission: Buying Information

A spike is not “go build a prototype.” It is a focused, time-boxed experiment—usually one to two weeks—where you stop building features and start building proof.

For CityPulse, I have the team focus on three explicit objectives:

- Build a “Walking Skeleton”: Implement the absolute minimum end-to-end ticket purchase flow. It does not need to be pretty; it just needs to prove that a message can travel from the API to the database via a broker.

- Expose the “Unknown Unknowns”: The biggest dangers are the problems you do not know you have yet. We focus on two areas: How do we trace a request across the system? And what does the debugging experience feel like?

- Measure the Friction: How steep is the learning curve? Where do the engineers get stuck? This is not about judging the team; it is about honestly measuring the “complexity tax” of the new paradigm.

The Logbook: Lived Realities of EDA

The two weeks are a whirlwind of learning. I watch as the team discovers the universal hurdles of adopting Event-Driven systems:

- Day 2: The Tooling Problem. The team hits a wall immediately. Their standard testing libraries do not support mocking the event broker well. Unit tests become non-intuitive and difficult.

- Day 5: The Observability Challenge. A subtle bug in an event schema takes nearly a full day to track down. The request looked “successful” at the API, but was failing silently in the background. They realize they have no way to tie the two events together.

- Day 9: The Mental Shift. The team gets the flow working, but during the review, a senior developer admits: “I am still struggling to reason about this. The idea that the purchase is not ‘done’ when the API call returns is giving me a headache.”

The Verdict: A Fork in the Road

At the end of the spike, you convene a retro. The walking skeleton works, but the journey was fraught with friction. The raw data is in, but the data does not make the decision. Now, your job is to interpret that data within the team’s specific context.

Path A: The Pragmatic Pivot

This team looks at the results and sees too much risk for a 3-month deadline. The testing and debugging friction is a direct threat to their velocity.

- The Log reads: “The spike told us what we needed to know. It converted the ‘unknown’ risk into a ‘known’ and unacceptable one. Charging ahead would be setting the team up for failure.”

- Decision: You pivot to a well-structured monolith for the launch, ensuring clean internal boundaries so you can extract services later.

Path B: The Confident Validation

This team sees the challenges as familiar, solvable problems. They decide to incorporate specific libraries for event mocking and enforce “Correlation IDs” for observability from day one.

- The Log reads: “The spike revealed no surprises. It validated that our existing skills are sufficient to manage the risk. We are ready to proceed.”

- Decision: You proceed with Event-Driven Architecture with the confidence that the “ghosts” have been identified.

Context is King

An architectural spike is not meant to prove your initial hypothesis right. Its purpose is to replace uncertainty with evidence.

As you have seen, the same evidence can lead to two different, entirely correct decisions. Path A was not a “failure,” and Path B was not “smarter.” They were different answers to the same question, tailored to the reality of the people who have to build the system.

In our next post, we will follow Path B and tackle the first challenge of implementation: Documenting the Decision.